The ship keeps the continent connected

BBC News, Accra

BBC

BBCA ship the football field, which is wandering by more than 50 engineers and technicians, is working on the oceans throughout Africa to keep the continent online.

It provides a vital service, as it showed the internet obstruction last year when the Internet cables were deeply affected by the sea.

Millions of Lagos were drowned to Nairobi in digital darkness: correspondence applications were crashed and banking transactions failed. Let companies and individuals struggle.

It was Léon Thévenin who fixed the failure of the multiple cables. The ship, where the BBC recently spent a week on the Ghana coast, is making specialized reform over the past 13 years

“Because, the two countries are in contact,” said Shoro Arndend, a useful cable from South Africa that works on board for more than a decade.

“People at home have a job because I bring the main feed.”

“You have heroes that save lives – I am a hero because I save the communication.”

His pride and passion reflects the feelings of the skilled crew on Lyon Thivinin, who stands eight floors and carries a variety of equipment.

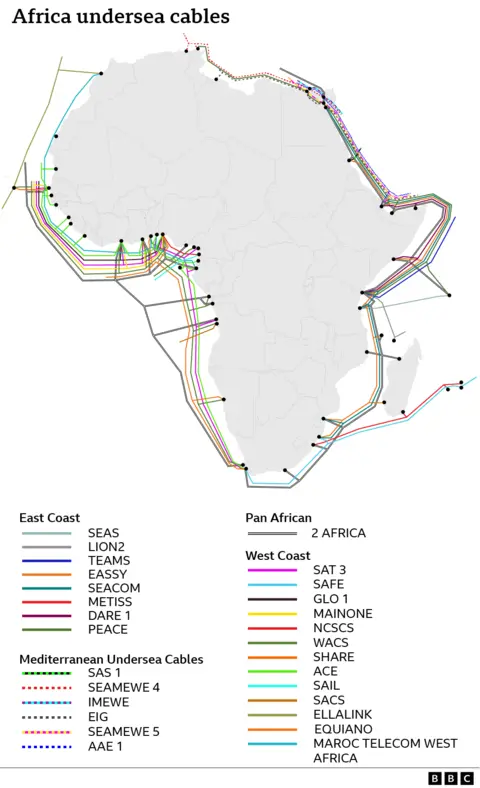

The Internet is a network of computers’ servers – to read this article, it is possible that one of 600 cables of optical fiber all over the world collected data to present it on your screen.

Most of these servers are present in databases outside Africa, and the optical cables fiber are running along the ocean floor that connects them to the coastal cities on the continent.

The data is transmitted via the thin glass fiber wires, and is often collected in pairs and protected with different layers of plastic and copper depending on the extent of the cables near the beach.

“As long as the servers are not in the country, you need a connection,” Benjamin Smith, Vice President of Lyon Thaenin, said.

Fiberial cables are designed under the surface of the sea to work for 25 years with minimal maintenance, but when damaged, it is usually due to human activity.

“The cable is generally not separated on its own unless you are in an area with high currents and very sharp rocks,” says Charles Hilde, who is responsible for the vehicle that is operating remotely (ROV).

“But most of the time, the people who prove where they should not and hunting hunting sometimes along the sea floor, so we usually see scars of hunting.”

Mr. Smith also says that natural disasters cause damage to cables, especially in parts of the continent with harsh weather conditions. It gives an example of the seas off the coast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the Congo River is emptied in the Atlantic Ocean.

He says: “In Cono Canyon, where they have a lot of rain and low islands, it may create the currents that harm the cable,” he says.

It is difficult to determine deliberate sabotage – but the Léon Thévenin crew says they have not seen any clear evidence of this themselves.

A year ago, three critical cables in the Red Sea – Seacom, AAE -1 and Eig – It was cut, and according to what is said by the ship’s anchorCalls in millions throughout East Africa, including Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Mozambique.

Just one month later, in March 2024, a separate group of separators in WACS, ACE, SAT-3 and the main cables off the West Africa coast caused electrical power outage via online via across Nigeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast and Lubiria.

Anything that requires the Internet to press with the extended repairs for weeks.

Then in May, another setback: Seacom and ESSY cables from South Africa coast suffered, where the connection was struck in the multiple countries of East Africa again.

These defects are discovered by testing electricity and signal transfer power via cables.

“There may be 3000 volts in the cable and suddenly it decreases to 50 volts, and this means that there is a problem,” explains Luke and Ward, head of the ship’s mission.

There are local teams that have the ability to deal with errors in shallow water, but if they are discovered beyond a depth of 50 meters (164 feet), the ship is called to work. Its crew can fix the cables deeper than 5000 meters below sea level.

It took more than a week to reform in Ghana, but most Internet users were not noticed as traffic was re -directed to another cable.

The nature of each repair depends on the damaged cable.

If the glass fibers are in the basic breaks, this means that the data cannot be transmitted along the network and you need to send it to another cable.

But some African countries have only one cable that serves them. This means that the damaged cable in this way leaves the affected area without the Internet.

At other times, the fiber protective layers can be damaged, which means that the transfer of data is still happening, but with less efficiency. Either way, the crew must find the exact position of the damage.

In the case of fiberglass broken, the light signal is sent through the cable and through the reflection point, the crew can determine the location of the break.

When the problem is with the cable insulation – known as the “conversion error” – it becomes more complicated and an electrical signal must be sent along the cable to track materially where it is lost.

After narrowing the possible area of the error, the process is transferred to the Rove team.

ROV, which weighs 9.5 tons, such as the bulldozer, is designed underwater from the ship where it is directed to the ocean floor.

About five members of the crew work with a crane operator to publish it – as soon as it is launched from its harness, it is called the umbilical cord, it floats safely.

“He does not drown,” says Mr. Hilde.

The three Roof cameras on board the plane allows the search for the exact location of errors as it moves to the ocean bed.

Once it is found, ROV cuts the affected part using its arms, then connects it with a rope that is dragged to the ship.

Here the defective section is isolated and replaced by linking and joining it into a new cable – a welding -like process that lasted 24 hours in the case of the process in the BBC.

After that, the cable was carefully lower to the ocean bed, then ROV made a last trip to inspect it in a good position and take coordinates so that the maps could be updated.

When an alert is received around a damaged cable, the Léon Thévenin crew is ready to sail within 24 hours. However, the time for their response depends on several factors: the location of the ship, the availability of spare cables and bureaucratic challenges.

“The permits can take weeks. Sometimes we sail to the affected country and wait abroad until the paper works are sorted,” says Mr. and Al -Harand.

On average, the crew spends more than six months at sea every year.

“It is part of the job,” says Captain Thomas Quick.

But talking to the crew between the tasks, is difficult to ignore their personal sacrifices.

It is drawn from different wallpapers and nationalities: French, South Africa, Filipino, Malagia and more.

Adrian Morgan, South Africa’s chief South Africa, missed five consecutive marriage.

“I wanted to smoke. It was difficult to get away from my family, but my wife encouraged me. I do it for them.”

Another from South Africa, the tested of maintenance, Noel Joyman, is concerned that you may miss his son’s wedding within a few weeks if the ship is called to another mission.

“I heard that we might go to Derban (in South Africa). My son will be very sad because he has no mother,” says Joiman, who lost his wife three years ago.

“But I am retired in six months,” he adds with a smile.

Despite the emotional losses, there is an intimate friendship on board.

When it is out of service, crew members either play video games in the hall or share meals in the chaos in the ship.

They enter the profession are varied as their background.

While Mr. Joiman followed his father, Cook President, South Africa, Remario Smith, went to the sea to escape the life of the crime.

“I participated in the gangs when I was younger,” Smith says. “My child was born when I was 25 years old, and I knew that I had to change my life,” Smith says.

Like others on the plane, it appreciates the role the ship plays on the continent.

“We are the relationship between Africa and the world.”

Participated in additional reports by Jess Euerbach Jahjaya.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC