Afghans are hiding in Pakistan, who live in fear of forced deportation

BBC News, Islamabad

BBC

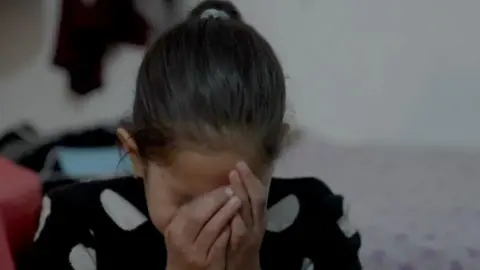

BBC“I am afraid,” Nabila sighed.

The life of the 10 -year -old girl is limited to her one -bedroom home in Islamabad and the soil road outside. Since December, she did not go to her local school, when she decided that she would not accept Afghans without a valid Pakistani birth certificate. But even if you can go to the classroom, Nabila says she will not do that.

“I was one day sick, and I heard that the police were looking for Afghan children,” she was crying, and she tells us that her friend’s family had been sent to Afghanistan.

Nabila is not her real name – all the names of Afghan adapted in this article have been changed for their safety.

The United Nations says that the capital of Pakistan and the neighboring city of Rawalpindi are witnessing an increase in deportations, arrests and detention from Afghans. It is estimated that more than half of three million Afghans in the country are not documented.

Afghans describe a life of constant fear and near the daily police raids on their homes.

Some have told BBC that they are afraid to kill them if they returned to Afghanistan. These families include the American resettlement program, which were suspended by the Trump administration.

Philipa Candler, representative of the United Nations Refugee Agency in Islamabad, says Pakistan is disappointed by the period of transportation programs. The United Nations Immigration Organization (IOM) says 930 people were sent to Afghanistan in the first half of February, twice the shape two weeks ago. At least 20 % of those who were deported from Islamabad and Rawalpindi were documenting the United Nations Refugee Agency, which means that they were recognized as persons needing international protection.

But Pakistan is not a party to the Refugee Conference, and it has previously said it does not recognize the Afghans living in the country as refugees. The government said that its policies aim to all illegal foreign citizens, and a deadline for departure is made. This date has been fluctuated but was now appointed to March 31 for those who do not have valid visas, and June 30 for those who have resettlement messages.

Many Afghans are terrified amid confusion. They also say that the visa process may be difficult to move. Nabila’s family believes that they have only one option: hiding. Her father, Hamid, served in the Afghan army, before the Taliban acquired in 2021. He collapsed in crying, describing his sleep nights.

“I have served my country and now I am useless. This job has gone away,” he said.

His family without visas, and not listed in the resettlement list. They tell us that their phone calls to the United Nations Refugee Agency have not been answered.

BBC has reached the agency for comment.

The Taliban government told the BBC that all Afghans should return because they “can live in the country without any fear.” You claim that these refugees are “economic immigrants”.

But a United Nations Report in 2023 Doubt over assurances from the Taliban government. Hundreds of former government officials and members of the armed forces have been killed despite the general amnesty.

The Taliban government guarantees are a little reassurance to the Nabila family, so they choose to run when the authorities are close. Neighborhoods offer each other, as they all try to avoid re -satisfaction to Afghanistan.

The United Nations calculates 1,245 Afghans being arrested or detained in January via Pakistan, more than twice the period last year.

Nabila says that the Afghans should not be forced to go out. “Do not expel the Afghans from their homes – we are not here to choose, we are forced to be here.”

There is a feeling of sadness and loneliness in their home. “I had a friend here and then he was deported to Afghanistan,” says Maryam Maryam, Nabila’s mother.

“It was like a sister, a mother. The day was a difficult day.”

I ask Nabila what you want to do when you are older. “Modeling”, as you say, gave me a serious look. Everyone in the room smiles. The melting of tension.

Her mother whispered to her there is a lot of other things that can be, engineer or lawyer. Nabila’s dream of modeling is a dream that he can never follow under the Taliban government. Thanks to their restrictions on girls’ education, her mother’s suggestions are also impossible.

New stage

Pakistan has a long record of seizure of Afghan refugees. But the cross -border attacks rose and tense between neighbors. Pakistan blames them for gunmen based in Afghanistan, which is denied by the Taliban government. Since September 2023, the Pakistani year has launched the “Restoring Plan for illegal Foreigners”, 836,238 individuals have now been returned to Afghanistan.

Amid this current stage of deportation, some Afghans are held in Al -Hajji camp in Islamabad. Ahmed was in the final stages of the United States Resettlement Program. He tells us when President Donald Trump was suspended for the review, he extinguished the “Last Hope” Ahmed. The BBC has seen what it appears to be a letter of employment by a non -profit Western group in Afghanistan.

A few weeks ago, when he was out of shopping, he received a call. His three -year -old daughter was at stake. He says, “I called my child, come to the Baba police here, the police come to our door,” he says. The extension of his wife’s visa was still suspended, and it was busy begging with the police.

Ahmed ran to the house. “I couldn’t leave them behind them.” He says he sat in a truck and waited for hours while the police continued their raids. The wives and children of his neighbors continued to flow into the car. Ahmed began receiving calls from their husbands, and begged him to take care of them. They already fled to the forest.

Ahmed, who claims that one blanket has been granted to each family, one piece of bread per day, and that their phones are confiscated. The Pakistani government says it guarantees “no one is subject to abuse or harassment during the process of returning the homeland.”

We are trying to visit inside the Hagi camp to verify Ahmed’s account, but they are rejected from entering the authorities. BBC approached the Pakistani government and the police to conduct an interview or a statement, but no one was provided.

Fear of detention or deportation, some families have chosen to leave Islamabad and Rawalpindi. Others tell us that they simply cannot afford.

One of the women claims that she was in the last stages of the American resettlement scheme and decided to move with her two daughters to Atok, 80 km (50 miles) west of Islamabad. “I can barely bear bread,” she says.

The BBC witnessed a document confirming that it had an interview with the International Organization for Migration in early January. She claims that her family is still witnessing almost daily raids in her neighborhood.

A spokesman for the American embassy in Islamabad said that in “close communication” with the government of Pakistan “about the situation of Afghan citizens in the American resettlement paths.”

Outside the doors of Hagi Camp, a woman is waiting. She tells us that she has a valid visa, but her sister has expired. Her sister is now being held inside the camp, with her children. The officers did not allow her family to visit, and she was terrified to be deported. She started crying, “If my country was safe, then why did I come to Pakistan? And even here we cannot live in peace.”

She refers to her daughter sitting in their car. She was a singer in Afghanistan, where a woman who cannot hear a woman cannot speak outside their home, not to mention singing. I go to her daughter and ask if she is still singing. It is staring. “no.”